JOURNEY

Origin

In the Haida language, K’uuna means “edge” and Llnagaay means “village” or “town.” The name of the village reflects its position on the northeast edge of Louise Island, at the head of Cumshewa Inlet in the group of islands called Haida Gwaii, off the northern coast of what is now British Columbia.

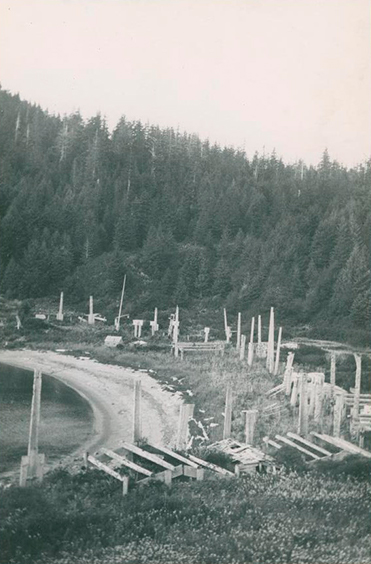

The village had been laid out centuries before with houses of the Eagle clan to the west, houses of the Raven clan to the east, and the village chief’s house in the center. By the time George M. Dawson photographed the village for the Geological Survey of Canada in 1878, it was called Skedans, after the village chief, Gida’nsta. It was known locally as K’uuna Llnagaay and also SXuu.ajoo Llnagaay (Grizzly Bear Town). Dawson wrote, “Many of the houses are still inhabited, but most look old and moss-grown, and the carved posts have the same aspect.”

Between 1836 and 1841, about 439 people lived in K’uuna Llnagaay. There were 16 houses and 44 poles there in the 1870s. Ten years later there were no permanent residents at K’uuna. Disease and other impacts of colonization had greatly reduced the population, and people were moving away to other villages, first to Cumshewa and then to Skidegate.

Poles and houses at K’uuna Llnagaay (Skedans), July 18, 1878.

George M. Dawson photograph. BCA C-09259.

K’uuna Llnagaay looking west from the hill behind the village, 1902. Charles F. Newcombe photograph PN 10.

A house frame at K'uuna Llnagaay with frontal pole flanked by mortuary poles, 1901. British Columbia Bureau of Mines. I - 56098.

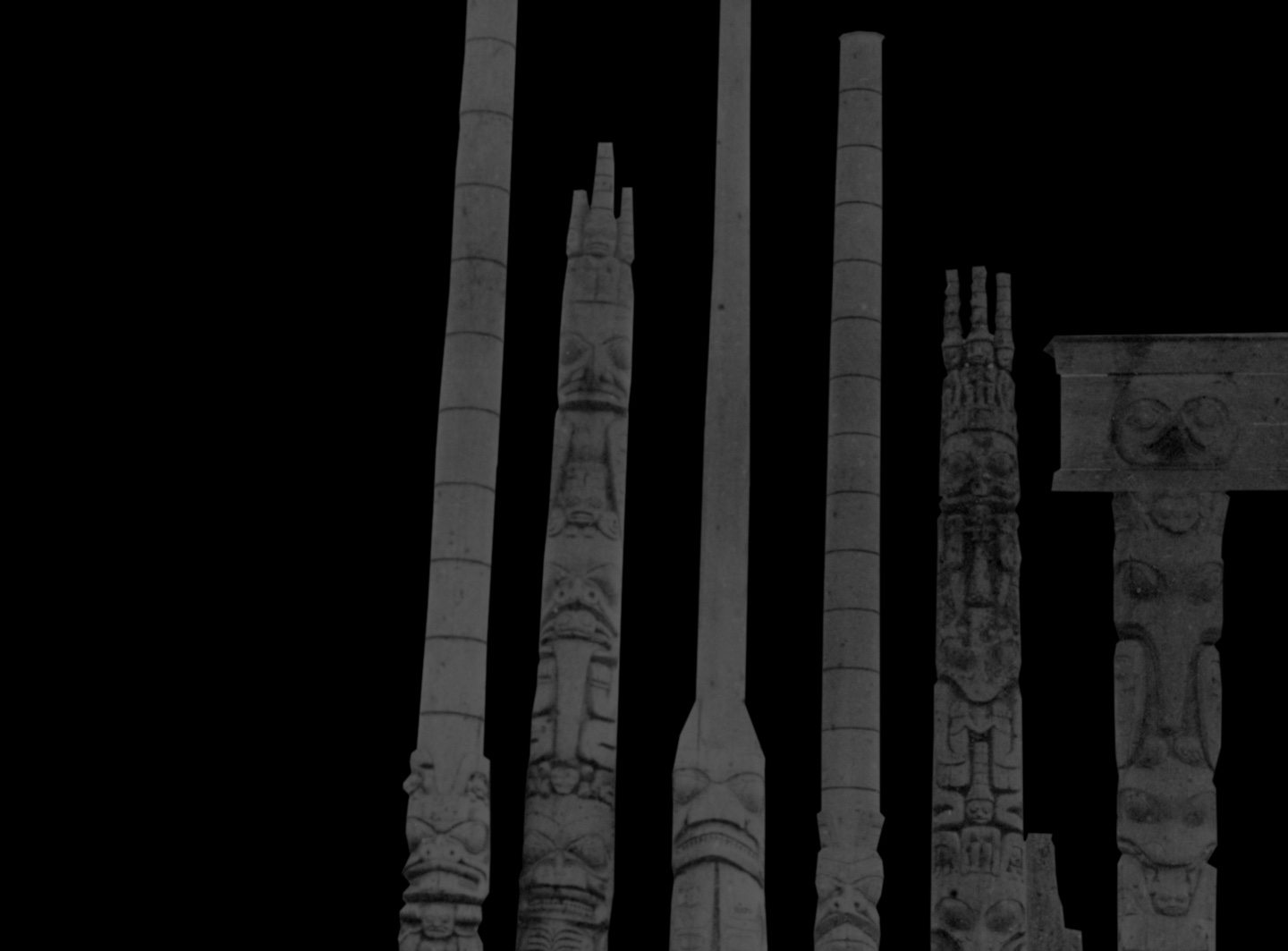

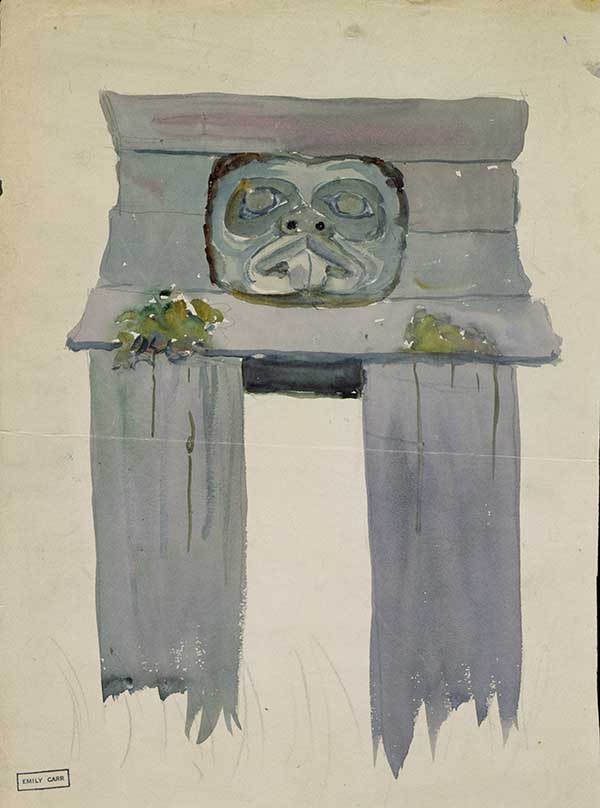

Early in the 1900s, artist Emily Carr visited K’uuna Llnagaay, and was fascinated by the poles still standing in the abandoned village. She captured their haunting beauty in sketches and watercolours, several of which are in the collection at the Royal BC Museum

Emily Carr made several paintings of K’uuna Llnagaay. This photograph was taken during one of her visits, around 1912. PN 9680.

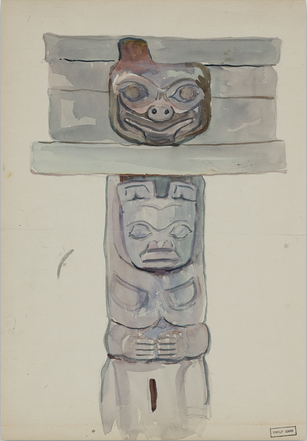

Emily Carr, “Skedans Poles, Queen Charlotte Island,” watercolour on paper, 1912. PDP02310.

Emily Carr, sketch of a mortuary pole at Skedans, watercolour on paper, 1912. PDP0 2303.

Emily Carr, sketch of a mortuary pole at Skedans, watercolour on paper, 1912. PDP02308.

Emily Carr, sketch of a mortuary pole at Skedans, watercolour on paper, 1912. PDP02301.

JOURNEY

Removal

In 1935, the City of Prince Rupert removed house frontal poles from K’uuna Llnagaay and erected them in a city park. In 1954 the provincial Totem Pole Preservation Committee was established to salvage deteriorating poles from coastal villages, and ensure they were cared for. Their first removals of poles from Haida villages were at T’anuu Llnagaay (Tanu) and K’uuna (Skedans). They went on to remove poles from SG̱ang Gwaay Llnagaay (Ninstints) on Anthony Island in 1957. The poles were taken to the museums in Victoria and Vancouver.

In 1964 and 1965, the K’uuna poles that had been taken to Prince Rupert came to the Royal BC Museum. The museum repatriated them to the Haida Nation in 1976, except for a carved Eagle from a K’uuna grave house and fragments of the Grizzly Bear pole, which were put into protective storage.

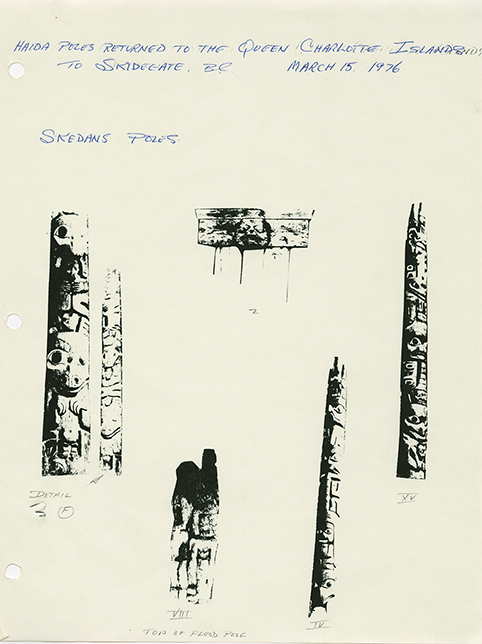

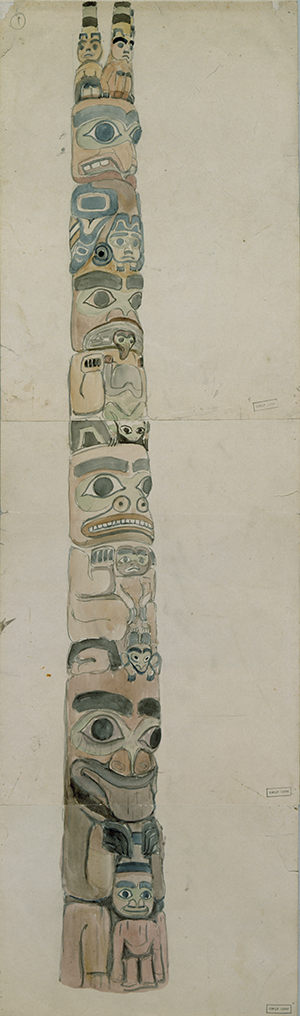

John Smyly, the museum technician who made the model of K’uuna Llnagaay, made this drawing of the poles from K’uuna that were repatriated from the Royal BC Museum to Haida Gwaii in 1976.

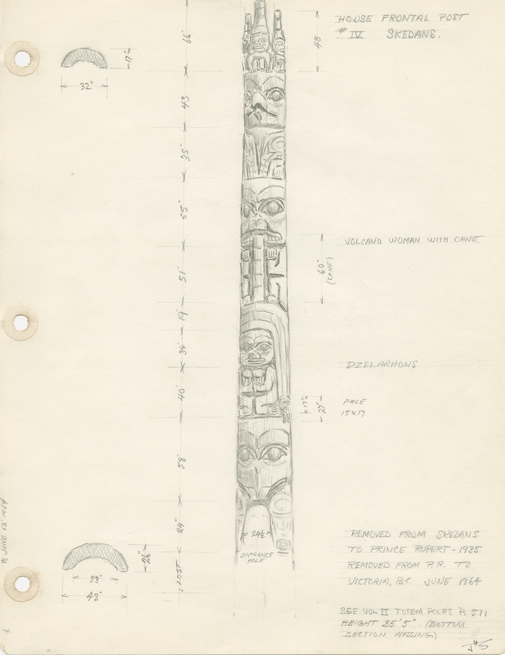

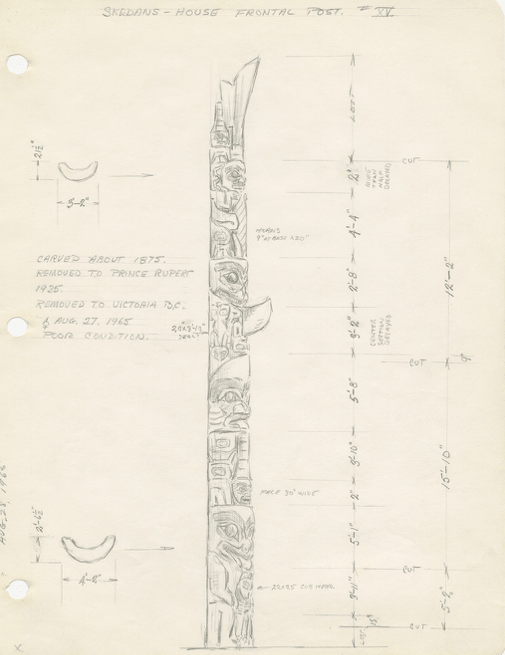

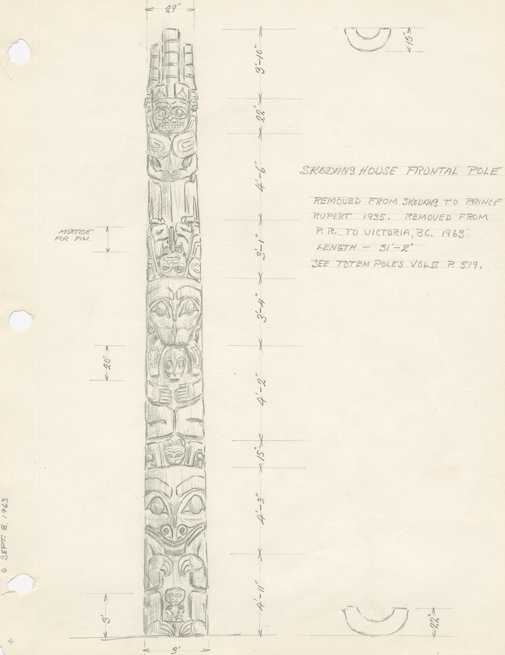

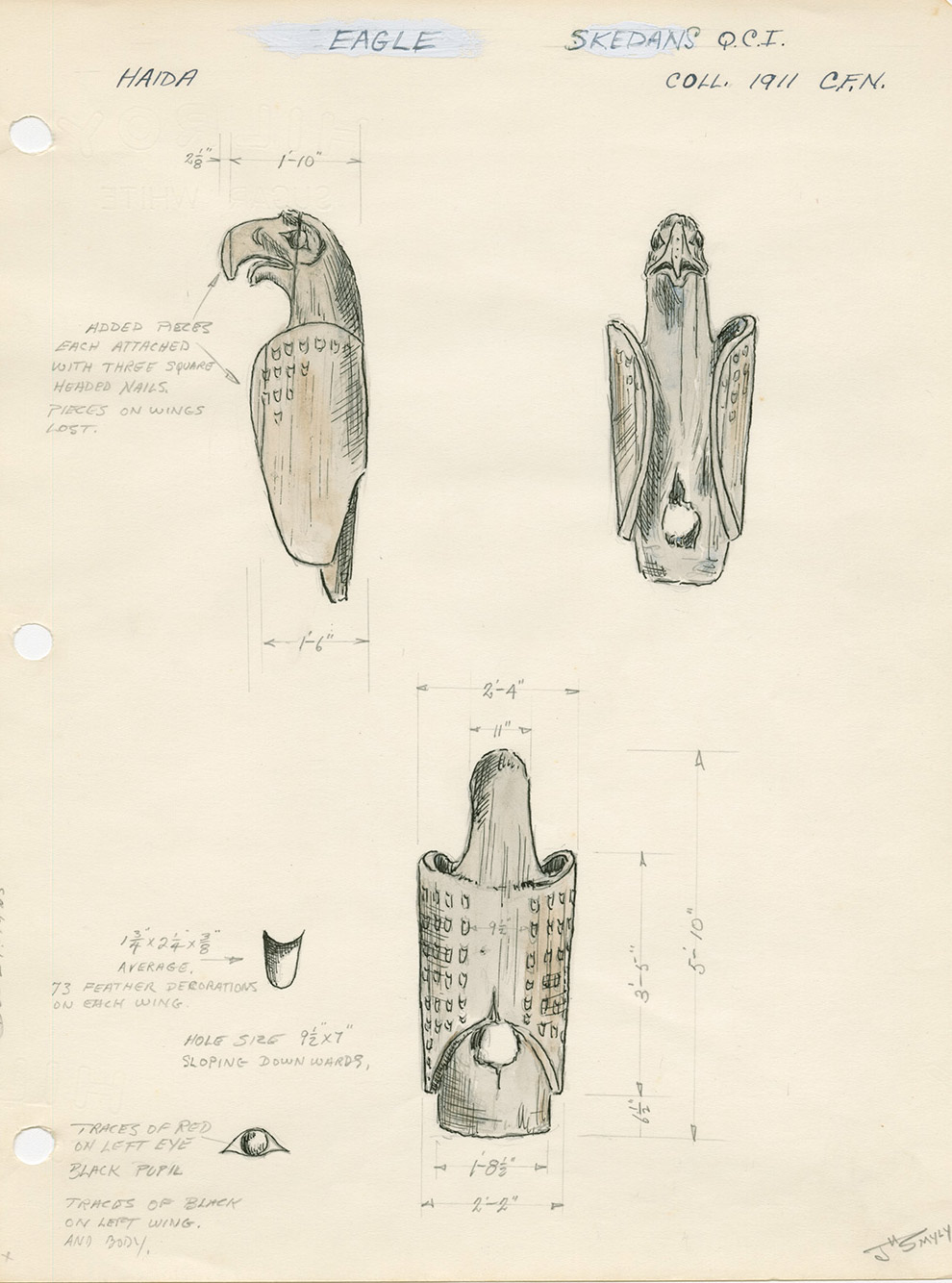

John Smyly’s drawings of one of the K’uuna Llnagaay poles that came to the Royal BC Museum from the city of Prince Rupert in 1964 and 1965.

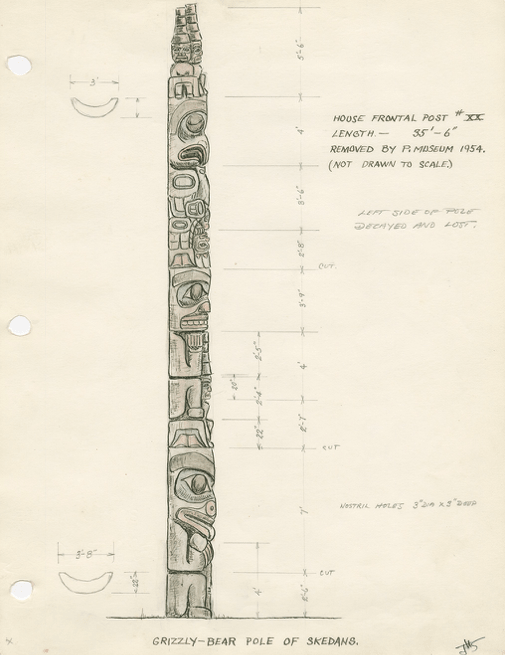

The Grizzly Bear pole was sketched at K’uuna Llnagaay by Emily Carr in 1912 (PDP03177) and by John Smyly after it came to the Royal BC Museum. A replica of this pole made in the Royal BC Museum’s carving program by Mungo Martin with Bill Reid stands at the Peace Arch international border between BC and Washington State.

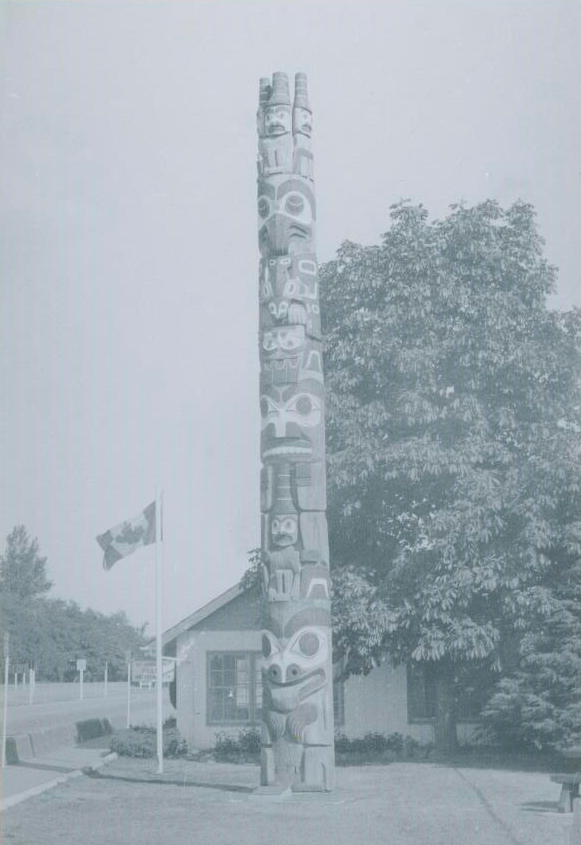

The replica of the K’uuna Grizzly Bear pole by Mungo Martin and Bill Reid at the Peace Arch Park, 1967. PN 6177-20.

John Smyly’s drawings of a carved Eagle removed from K’uuna Llnagaay in 1954 by the Totem Pole Preservation Committee and now in storage at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM 15561).

The Grizzly Bear pole that was removed from K’uuna Llnagaay in 1954 by the Totem Pole Preservation Committee is in storage at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM 15560).

The model is on display in the First Peoples gallery.

When the Royal BC Museum’s First Peoples Gallery opened in 1977, the centrepiece was a scale model of K’uuna Llnagaay as it looked in the late 1800s. Museum technician John Smyly had painstakingly created the model over five years, working mainly from photographs taken of the village by George Dawson in 1878 and from measurements taken at the site.

In September 2018, thanks to detailed input from Guujaaw, Haida artist, leader and hereditary Chief Gidansda, the museum has added fresh new audiovisual and textual material alongside the model village, providing an authoritative perspective and deeper cultural context.

JOURNEY

Today

At the time of Dawson’s visit, the islands were called the Queen Charlotte Islands, after the British queen consort to King George III. In 2010 that the name was formally changed to Haida Gwaii, meaning “islands of the Haida people,” the place where Haida people have lived for many thousands of years.

Although most of the K’uuna sculptures have returned to the earth or been removed, K’uuna Llnagaay is one of the few remaining Haida village sites with standing totem poles and remnants of large longhouses.

A pole returning to the earth. The shells were placed to mark a path for visitors to the site. Patrick Shannon photograph, July 2018.

Chief Gidansda, also known as Guujaaw, the hereditary chief of K’uuna, and his great-nephew Tian Wilson at the site in July 2018. The Haida Watchman’s building is in the background. Patrick Shannon photograph.

At the top of most Haida poles there are Haida Watchmen, small human figures—usually three, sometimes fewer—wearing high striped hats. They represent the Haida watchmen who in the past were posted at strategic positions around a village to raise the alarm in advance of an approaching enemy. Now K’uuna is by protected under the Haida Gwaii Watchmen Program, which runs from May to October. A Haida Watchman leads visitors along a path that winds through the old village, allowing them to wander through the site and appreciate the artistry of the poles, now in varying stages of decay.

Ḵ’uuna Llnagaay is within the Haida Heritage Site but outside the boundaries of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and National Marine Conservation Area Reserve. Descendants of the village now live in Skidegate and Masset, but they remain people of K’uuna.

CONNECTIONS

Related Carvings

Amelia Rea

Amelia Rea – Gudanee Xahl Kil

Amelia Rea is an 18-year-old youth from Haida Gwaii. She belongs to the Ts’iits G’itanee Eagle clan and descends from Lucy Frank.

Amelia is an advocate for Haida language and culture. She grew up going to language camps, classes and conferences with her mom. She won the Tahayghen Rosa Bell Haida Language award and was the top student in her Haida language class. Her voice can be heard in the Haidawood Yaanii K’uuga animation. Being beside her mom has led her to co-present her mom’s Haida Language Revitalization thesis at UVIC, the International Conference of Language Conservation and Documentation and at the International Haida language conferences.

She has performed in many traditional Potlatches and has traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian, the American Museum of Natural History, the Canadian Museum of Civilization and Celebration in Juneau. She loves culture-sharing!

Amelia has also had excellent experience in visual Haida arts. From a young age, she learned how to weave, design button blankets and woodworking.

Amelia worked at the Haida Gwaii Museum in Skidegate during the summer and she volunteers at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria. She has a passion for learning and enjoys studying the ancient artworks of her ancestors. She recently shared Royal BC Museum artifact and language recording catalologues at Celebration in Juneau, AK and she advocates for research and repatriation.

In 2015, Amelia was on the winning team at the Haida Gwaii youth conference and was known for bravely giving speeches and following traditional protocol just like her great-great grandfather, Chief Weah.

Amelia has spoken at three International language conferences in BC and in Hawaii.

Explore a curated selection of Royal BC Museum objects and contemporary photographs that inspire this community member to continue working in the tradition of her Haida ancestors.

There were a lot of poles In Kuista

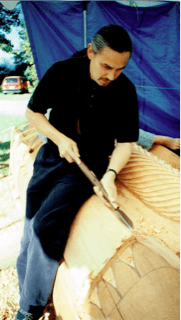

He carved the totem pole with a curved knife

The members of the opposite moiety used to do the work on the poles

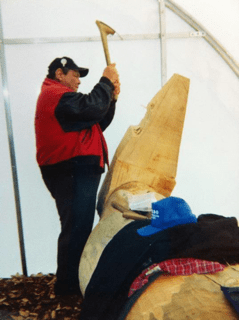

This is adze.

They will also raise a totem pole

The pole is twenty feet long

There are also a lot of poles at SGaan Gwaay

Here is a forest filled with totem poles.

She'll also carve totem poles

Carve it!

There was an eagle crest on top.

They called it a blessing

When they would raise a pole, it was hard work